In October 2022 the artistic intervention Parasite Parking reclaimed public space through activation and habitation. For 8 days, Parasite Parking squatted parking spaces in different neighborhoods in Chicago. Those parking spaces, formerly owned by the City, were privatized in 2009. With the 75-year lease of most of Chicago’s parking area, the non-democratic stakeholder ParkChicago became one of the main actors defining and managing big parts of the public space and its potential transformations. Due to the negotiation with ParkChicago and increasing costs related to the contract, parking spaces in Chicago cannot be easily transformed into bike lanes, gardening areas, or other types of public infrastructure and adaptations to urban and social needs.

Parking spaces are now one of the battlegrounds of the future city. They are a multiple border zone: between private and public; between staying and leaving; between the mobility of yesterday and the more climate-friendly alternatives of tomorrow; between privileged areas and areas of deprivation. Just like every other available space in the city, parking spaces are increasingly subject to gentrification and rent-seeking. However, they can also transform into a niche for budding new uses and create spatial potential for emancipatory practices.

Parasite Parking occupied these niches and explored their subversive potential. It provoked and worked on the attendant allowance of such a space. How far is it possible to expand the niche without being caught or expelled by the host (authorities)? How much can be executed without any permissions? Parasite Parking intervened in the public space by means of a multifunctional platform camouflaged as a parking space – a platform and container covered with concrete on the top surface, and clad in mirrored plates on the sides. The platform was thus able to adapt to its paved environment and was simultaneously ready to fold out into a space for various uses: a living space, a performance stage, a street assembly for activist meetings, a café for the neighborhood, or back into a conventional parking space.

Parasite Parking is an uninvited guest on the spaces that should be available to all of us, and yet are currently occupied only by the steel bodies of modernity.

Parasite Parking appropriates private space which used to be public. The parasite does not ask about ownership and its rules, but about the limits of making public space usable and about who holds and who can take public agency. Parasite Parking defamiliarizes the use of parking spots, overtaking and reclaiming nearly a third of urban spaces.

Moreover, the parasite asks what will happen to this privatized space if parking spaces are no longer needed at all. By using it in various ways, Parasite Parking works on de- and recoding parking spaces by introducing a new imagination of how we can redesign our public space.

Sup- ported by Mikle a neighboor: Parasite Parking pilled up on a pick-up, being transported from the Magnificent Mile to Down- town Chicago.

Parasite Parking in front of 6018 North in Edgwa- ter Chicago. Image info from right down: A guest drinking Champaign with the parasite. And Parasite Parking in its be- droom variation.

Parasite Parking in front of 6018 North in Edgwa- ter Chicago. Image info from right down: A guest drinking Champaign with the parasite. And Parasite Parking in its be- droom variation.

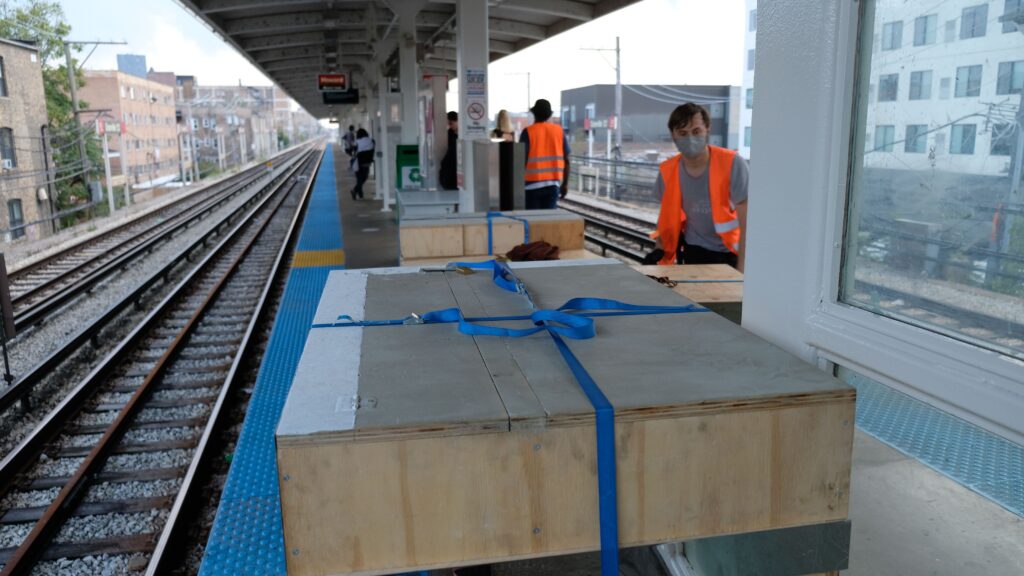

Moving the Parasite in public transpor

Moving the Parasite in public transpor

Moving the Parasite in public transpor

Missisippi, an activist and squatter of Campo Ponde- rosa invited Parasite Parking to join the camp for a night. Fighting against gentrification, homelessness, false imprisonment and police violence

Parasite Parking in Pilsen, Chicago. With tarp and licence plate

Public discussion about „Reclaiming the right to the city.“ In front of the city hall in down- town chicago.

Pa- rasite Parking in its camouflaged appearance: Town hall, Downtown Chicago.

Panel discussion with different artist and comu- nity organizers about Parasitic Strategies

Parasite Parking at Campamien- to Ponderosa, Squatted activist camp in Up- town, Chicago

Public Space of Chicago

The modernist city is not built for people, but for cars. Nothing shows this more like the countless parking spaces clogging up urban space. Between 50% and 60% of space in cities is used for cars, around 20-30% for their parking. So much more is possible in this space. In the same space, we could work, sleep, cook, make music, experience community – or simply be. This is exactly what the parasite does. In doing so, it wants to ask: who owns public space, who decides over it, and most importantly, who has access to it in the first place? Is the city built for humans or for cars?

The first site for the new parasitic action is Chicago, which is an extreme example of this issue. Due to a contract that leases parking space to various international private investors until 2084, the city has lost most of its control of and ability to transform the vast parking area in the city. The city cannot adapt easily to new needs of transportation, social life or ecology. With this loan, a public good has been sold which is elemental to public space. In the words of urban analyst Aaron Renn: “In effect, these deals aren‘t just about parking spots, they are assigning a property right interest in the biggest component of public space in the city to a private monopoly that doesn‘t have the public‘s best interests at heart.”

The parasite’s first parking experience

Parasite Parking started in front of 6018|North, an art space located in Edgewater, a diverse neighborhood despite the general wealth of the northern part of Chicago. By squatting this parking spot, Parasite Parking created space for meeting up with and between neighbors, in a street where this may happen between next-door neighbors at their garden fences but not so much between strangers and locals. It led to conversations about parking space, privatization of space and possibilities of micro-appropriation through small interventions like this – as well as to ordinary chats. The parasite was very shy at first, since it was not sure if people would complain about the missing parking space or if the occupation would lead to a fast complaint and eviction by the police. Surprisingly though, the intervention received barely a bad comment from passing cars, locals, or passers-by – even though parking spaces are lacking in that street.

Instead, the parasite was kindly provided for and supported by the neighborhood in different ways. People passed by to bring coffee, food, or equipment such as pots and candles; others supported the transportation of the parasite platform to the next parking site.

Interesting moments happened when cars just stopped beside the platform, lowered their window, and started a conversation about the parasitic intervention, even if a long queue of cars built up behind them. Such moments show that even as it was received with curiosity and friendliness, the Parasite actually irritated the neighborhood and its customary dynamics.

Parasite in Motion: Use of urban infrastructure – adapting to the host

A parasite can’t move without an external source of energy. If Parasite Parking wants to move, it needs to use an existing and already active infrastructure. The public transportation system seemed to be designed for the parasite. In its movable shape, stacked in container modules, Parasite Parking fit perfectly inside train station elevators and CTA train cars, where the parasite made use of the wheelchair infrastructure.

The parasite always depends on a host and on the ability to move away before being expelled, so modes of transportation are core to its design. Parasite Parking is constructed in the standardized dimensions of a euro-pallet, which also made it easy to ship it in a container ship and to use conventional transportation infrastructure.

Apart from its adaptable size and its ability to use existing routes, another defining characteristic of the parasite is a bold attitude. Niches are hardly found coincidently, an active search and sometimes even a concrete engagement are needed to open up a niche. In the case of public transit in Chicago, the parasite used its cultural capital and referred to its connection to the Chicago Architecture Biennial to give the project the gleam of official authority and give CTA staff a reason for their own support in moving the structure and a legitimation for doing something outside the norms.

In this case, niche and privilege are not far apart. If you are privileged, you can raise different arguments and be believed on the level of argumentation, as was the case when convincing CTA staff members to transport the parasite. By contrast, if you are not privileged with the base credibility of skin color, language, gender, or an institutional affiliation, arguing may lead nowhere other than further distress.

This is a point where I as an artist must frequently question the concept of the parasite; I would still think that it is easier to apply to a white person, coming from Germany, than to a person of color, who might still have to fight against the image and racism of being a parasite to society.

And the question always remains over whether a parasite exploits or gets exploited – it can be described in both ways.

The camouflaged parasite: Reinventing the logic of the host

Parasites live in spaces where the host can’t see them or where it can hardly fight them. In order to expand and to open up a niche, one of the parasite’s strategies is to imitate parts of the logic of the host. Parasite Parking uses a concrete-paved surface and mirrored sides to adapt to its environment and to be able to go unnoticed.

The parasite does what is needed to make its camouflage more effective and at the same time to expand its niche as much as possible. Because if we see the niche as a free space (or a legal vacuum); indeed as a heterotopia, since it doesn’t fall into the usual norms, laws and paradigms for the use of public or private space, then it has to be able to do both. It must be able to totally disappear in case the host comes looking for the niche – and to totally cause chaos while the host is occupied somewhere else. Like the mouse which throws a food party as long as the host is not in the kitchen.

In the case of Parasite Parking, this means that the parasite pays parking fees as long as

officers threaten to come, as that can effectively disarm any argument for eviction. It also has a license plate to adapt even more to the norms of appearance and registration of cars that occupy parking spaces. The potential of a parasite lies in its subversiveness and surprise. It eats from its host‘s pantry when they doesn’t expect it.

The parasite does not use direct forms of protest, even if it could have the same outcome.

Parasite and Persona

The parasite works and lives as a social and artistic figure or persona. The artist, me, is not the main actor – I stay in the background and only activate through living in the parasite; I cohabitate. But the artist is not the parasite, despite Tricia van Eyck´s question, “Who is the parasite?”. The parasite is defined by its relation, not through its materiality. Therefore you can define both of them as parasites.

There is also a host-parasite relation between me the artist and the parking parasite – we are both dependent on one another. I can‘t live on the street without the parasite, I won‘t be an artist without the platform and couldn‘t sustain myself on the street. On the other hand, the platform needs me to move on, and to get their parking fees paid.

Cohabitation: Campo Ponderosa – Question of appropriation, tokenizing, and social experiment

The artistic practice of Parasite Parking implies the experience of living in the streets for a certain amount of time. This practice can be seen as a social experiment, a situationist exercise, an activist intervention, or a perverse social tourism created out of a privileged situation. It is clear that it is a conscious process and a choice; that I, the artist, was not forced to live on the streets and that there is always an exit point. However, the project is not about the experience of sleeping on the street, or about enacting another reality lived by sections of the city’s populace. Rather, the project seeks to break shared norms for the use of parking and of public space, and to pervert the overuse of public space for cars, speculation, or privatization, instead of human needs. Dwelling in the project is also a strategy to ensure that the intervention can endure for longer periods, in comparison to a static object intervention, which doesn‘t have many rights to lose or to claim; by contrast, to remove me, while I am sleeping there, could be more difficult for authorities. That is a hypothesis, which hinges on both moral and practical considerations about humans and things in public space. It is true that a car wouldn‘t have problems occupying that space.

On the streets, I experienced the big gap of structural inequality, which differentiates me, with my privilege, from a person without shelter, as we do the same thing. I was in direct contact and we spent time together in the streets, drinking coffee, or having a chat. I built up trust with people around me which led to an invitation from Mississippi, an activist “leader” of Campo Ponderosa – a small squat on a parking lot under a bridge in Uptown Chicago – where activists and people without shelter live and claim space against the dynamics of gentrification in the neighborhood. There I spent one night, having dinner and exchanging ideas about counter-gentrification strategies in Berlin and Chicago.

The discourse of identity politics and the critique of experiencing something outside your own reality is another big discussion which is beyond the scope of this article. It is interesting, though, to observe from whom or out of which position the critique of appropriation comes from. I was not criticized (for engaging in another concern) in the public space, by passers-by or by the people who lived on the streets, but on social media, and by people who don‘t have an experience of homelessness.

This led me to conclude that the people who live on the street can grasp and observe the attitude of the parasite quickly. They can perceive if an action is “authentic” – to once use that problematic term – or only affirmational or extractive towards their own lived reality. They know, because they are in the best position to say so, if an intervention is or is not about faking their experience, appropriating their way of living, or utilizing their stories for another, personal or unrelated goal.

They could have seen my work as appropriative, and revealed to me something that I did not see. But as the residents of Campo Ponderosa, like Mississippi, felt positively about the nature of my work, they respected me and invited me to their own occupation.

The most important for such delicate interventions is the attitude with which you work – the way you approach and listen to people in spaces outside your “own” – and that the work is open whilst being defined in its questions.

Parasite vs. Authorities – “This is not a vehicle”

“This is not a vehicle”. We heard this a couple of times from a City officer whose function, although he was not a police officer, was to guarantee public order. Once the parasite has been spotted, its niche is gone, and it has to move. That member of city staff followed Parasite Parking for a couple of days and found it in two different areas downtown. He was not amused and wanted to bring it to an end, but was not sure which rule he could apply; it seemed he only knew that something was wrong. On the first day, he appealed to disorder in the public space, disturbance of the public order, and danger to the traffic. Thereby, he affirmed for Parasite Parking the essential trait of a parasite, which is to create disorder in a system and thus to stimulate entropy.

On the second day, the officer called more and more authorities from different public departments: the police, the city administration and the contracted staff of ParkChicago. Among themselves they debated rule breaking and what is allowed and what not. Eventually, the discussion hinged on whether the parasite is a vehicle or not. To be seen as a car, the parasite referred to its wheels and presented itself as a movable structure. Meanwhile, nobody knew exactly what definition of a vehicle was written in the contracts with ParkChicago. The question remained, who has the power to define what is a vehicle and what is not?

Reclaiming, taking or squatting space

When I first put the platform in a vacant parking space, I was a bit nervous. Questions came to my mind like, am I allowed to use this space? Is it okay to take so much space out of public infrastructure? Do I have the legitimacy to do this? I felt uncomfortable and again conscious of my privileges.

But after being there for a while, I noticed that the car in front of me didn’t move for the whole day and nobody questioned its existence. So I started to feel more entitled, and gradually more welcome in that space. I felt that my being also had value in the comparison of human vs. car, human space vs. car space.

Stigmatized Neighborhoods

The last station of Parasite Parking was in Pilsen, a traditional neighborhood, with a Mexican-American community that is undergoing a process of gentrification. This process has already pushed out many families to neighboring Little Village and other areas of the city. The neighborhood was known for gang violence, informal labor and insecure streets; while this profile has probably changed considerably, the stigma remains for people who live farther away – or for the police.

During my stay on the North Side and downtown, I never had real problems with the police. Already on the first night in Pilsen, the police arrived aggressively, with blue lights on, and halted by the platform, blocking the lane. The officer in the car informed us bluntly: either we leave in the next five minutes or we go to jail.

We listened and began packing up, but also continued to tell the officer about the project behind the platform – uncertain if the strategy could backfire. For the officer, the danger of Pilsen where he “attends calls for shots fired every night“ was both, a reason to expel us (it was unsafe for us, and that could create unsafe situations for even more people) and a reason to ridicule us, diminishing our defiance and improving our need for police-time in face of the more important crime scenes he should be heading to. Finally we managed to stay and the police disappeared, but this episode showed once again how strongly unequally the presence and attitude of the police is distributed in the city. According to our direct experience, the predominantly white North Side and wealthy downtown receive a more collaborative treatment from the police, with a two-way communication, opportunity for explanation and polite language. As we go further down, to the West and South Sides, the police become more aggressive, confrontational and unyielding.

Activation of parking space

At every site of intervention, Parasite Parking collaborated with different organizations of the respective neighborhood. In the old downtown location, Parasite Parking and the Chicago Tenants Union organized a political discussion and exchange about tenant strategies in Chicago and Berlin. In Pilsen together with Open Sheds Used for what we organized a panel discussion about counter strategies against privatization and spatial strategies of reclaiming public space. With NoNation Tangential Arts Lab, in Wicker Park, we organized a performance night to activate the street and transform it into a scenery. Other times, we did that by simply cooking dinner or making coffee and inviting people passing by. These actions led to a connection to the city, weaving the parasite’s yarn into the urban knit.