There is a kind of artistic freedom in dying without ever having an audience for your work. In one of his many unpublished manuscripts, my grandfather wrote: “His ship foundered, a delicate craft named, tentatively, Intelligence, in a sea that bubbled, like a seething and stinking cesspool, heated to a slow simmer, and kept heated, incessantly from the subterranean fires of suspicion, hate and fear—the sea of public opinion.” Now, what remains of his work are these inanimate brittle pages sitting in his granddaughter‘s lap. He wrote „Sometimes I wish I could be my own dummy sitting on my own knee.“ My knees are pale and round, unlike his dark and immobile knees, as I remember him sitting in his wheelchair. But my knees and I come from him, his progeny. Could I be the ventriloquist he once needed? Giving voice to the inanimate?

These are reckonings with what it means to be in relation to or with—specifically as an artist, writer, thinker, and descendant. I have recently considered parasitism as a kind of artistic strategy. Is ‘being in relation’ merely life as a parasite? Michel Serres wrote: “The theory of being, ontology, brings us to atoms. The theory of relations brings us to the parasite.”1 In this sense, is relationality an inevitability, or does true relationality require a sort of active reconciliation, an exchange with the other?

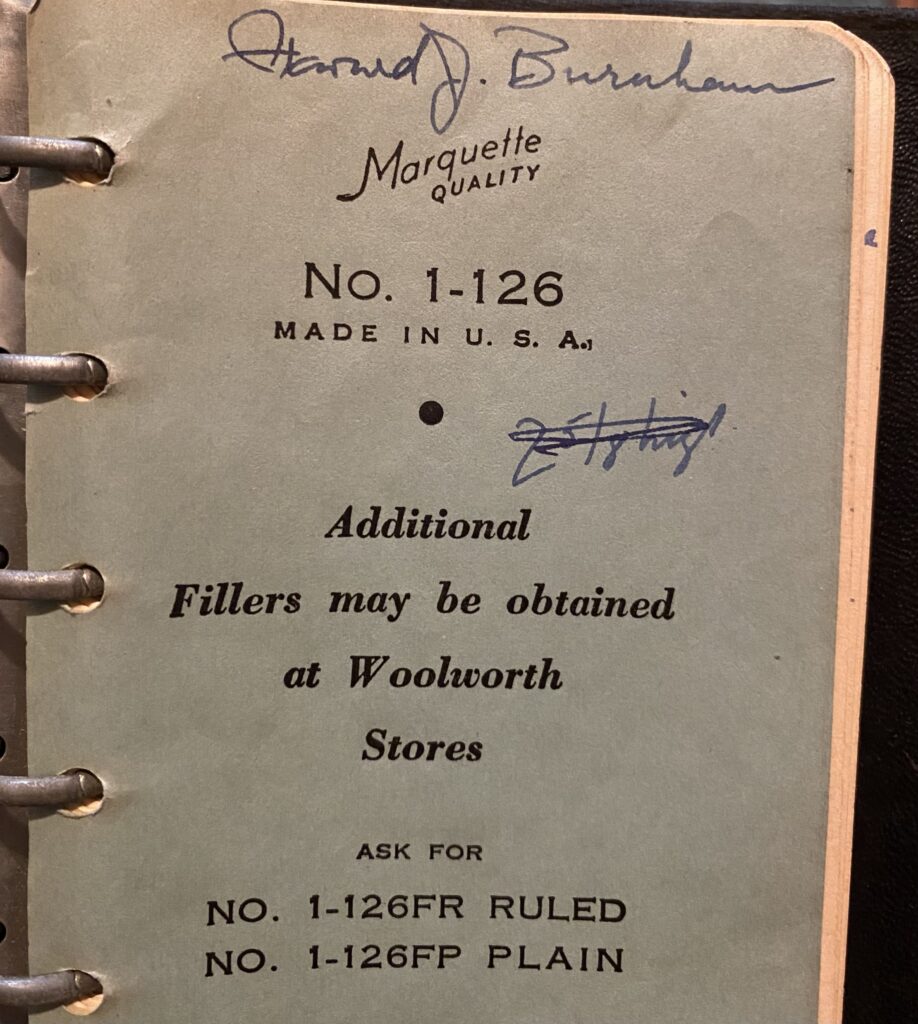

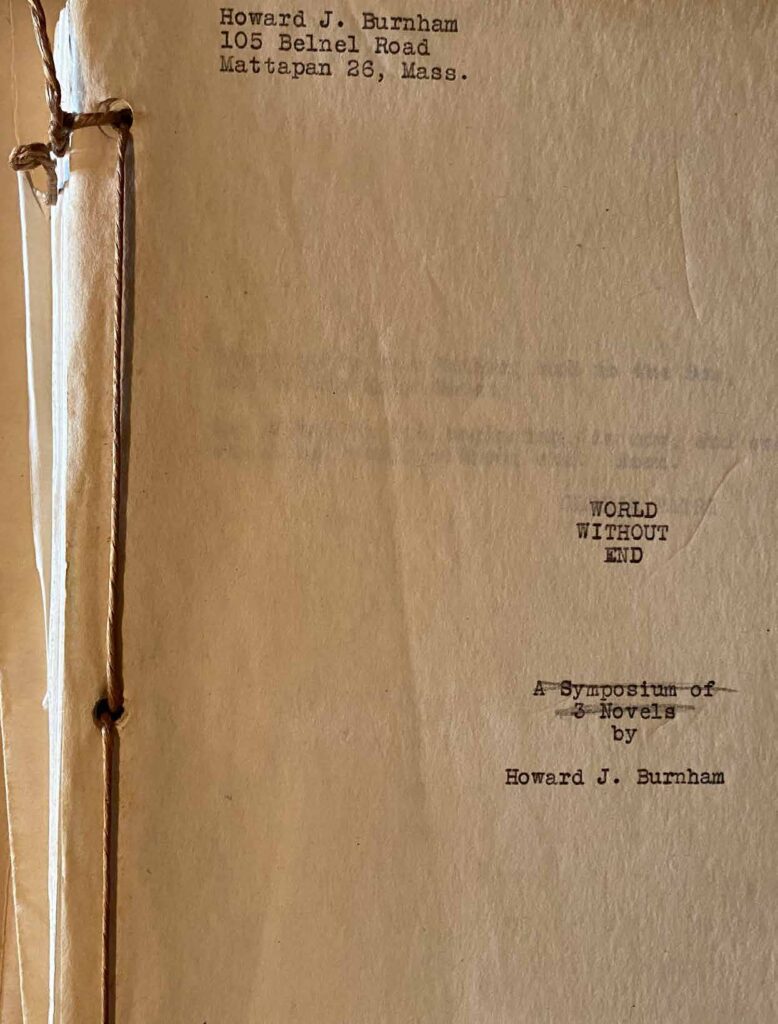

Horst Julius Emil Berman, or as he was known in the U.S., Howard J. Burnham, was „uprooted from his home and family“ when he was twenty years old. He „spent the next ten years—ten important…formative years…—being shoved back and forth over half of the globe.“

1955, typewritten:

„Today, more than fifteen years later, I am finally beginning to get my bearings. I am still an optimist—even more so than ever. I still have great trouble believing in myself. (…) but I have managed to somehow keep myself clear of entanglements, and still remain a part of society—how useful only the future will tell.“

To some extent, this is central to my query as his descendant—how ‘useful’ was he? The ‚freedom‘ he experienced after fleeing Nazi Germany permitted him to write, paint, procreate, and survive. Shortly after meeting my grandmother, they had three daughters, one of whom is my mother. My mother has had piles of his writing in her basement, which I recently retrieved.

I am collaborating with the deceased.

In her book Flesh of My Flesh2, Kaja Silverman argues that analogy is the basis of human relation. Through reckoning with our own mortality, one can recognize what Silverman calls their “ontological kinship” with another human.

Silverman:

“analogy is the correspondence of two or more things with each other, and it structures every aspect of Being”

“What distinguishes us from other creatures is our capacity to affirm these correspondences. Since we cannot affirm the analogies linking us to other people without acknowledging that we are bound by the same limits, we are reluctant to do so.”

As in, we avoid relationality because we are attempting to avoid reckoning with our own finitude.

Ovid:

“anxious in case his wife’s strength be failing and eager to see her, the lover looked behind him.”3

Silverman:

“Orpheus tries to ward off death by transforming Eurydice into a freakish member of another species; when he turns toward her, he therefore ‘sees’ not a fellow human being”

Once Orpheus himself dies he is able to truly see Eurydice as analogous to him—no longer looking back in fear, difference, or heroic ego. Only in death can they “celebrate their ontological kinship through a shifting but consistently transformative reenactment of what happened during their journey back to earth.”4

Silverman:

“When we turn away from someone, we cast her away. If we want to undo this destructive act, we must consequently not just turn around to face her but also behold her—embrace her with our look.”5 Is it possible for me to behold my grandfather through an analytical process?

My grandfather has been dead since I was eight years old. The single memory I have of him is of sitting at his kitchen table, playing a game where he would transform a scribble I’d draw into an identifiable image. While reading through stacks of his written work, I am myself concerned that I unfairly form an image of him based on his writings only, some of which are only scribbles in notebooks that he may have never wanted anyone to read.

Papa:

“At heart, I believe I am a rather “free spirit,” with a good artistic temperament. But the environmental restraints that were imposed on me, at an early age, and that brought the element of strict discipline and circumscription into my life, had a predominantly stifling effect on my natural artistic and emotional tendencies. It confined me always after.”

Silverman:

“As soon as the mirror asserts its exteriority, the infant self begins to disintegrate. Only by overcoming the otherness of its newly emergent rival [the mirror] can the child reassemble the pieces. (…) This rivalry makes similarity even harder to tolerate than alterity, since the more an external object resembles the subject, the more it undercuts the latter’s claim to be unique and autonomous.”6

Is the co-option of his writing the artist’s equivalent of a child continuing to run the family business after the loss of a parent? Or is it simply the typical referentiality of any making—the ongoing and inevitable artistic practice of parasitic influence and appropriation? Is it different when the content I am scavenging through is my grandfather’s?

The amazing thing about reading someone else’s writing, curated mostly by time and chance, is that one gets to witness opinions change, to see how they constantly contradict themselves.

In a letter from 1955: I am “in fact an optimist”.

Typed and compiled in 1963: “I am not a man of unfettered optimism”

And in a binder of typed aphorisms and reflections, embracing change:

“We need ideas more than facts, for facts are here today and gone tomorrow, but ideas may outlast generations, indeed grow stronger as time goes on.”

While Papa writes mostly about ideas, they often read as facts. I find that my style can exude a sense of certainty while the content revolves around relativity and groundlessness. Perhaps I inherit this stylistic quirk from him. I also have his hands, ridged thumbnails, and short arms, his smile (I think) and perhaps an intense feeling of self-doubt, that both my mother and I carry forth.

“Even in prosperity, I don’t believe it, and I am a rich man but I am a man of innate doubts. (…) I am jittery, especially as I buy my second car. I am moved to action by advertising slogans, for there is only the morrow—and no millennium in sight. Therefore I shall have to admit that I am a failure… a rich failure.”

Does my mortal perspective on the deceased’s work allow me to bestow value upon it and furthermore, value it as it becomes useful? If he were still alive, could I do this same thing? I often think about writing about my own father, and decide that I can not do so while he is still alive.

Photons are annihilated in our eyes when they hit our retina, in turn giving us sight—in the same way perhaps death enables life.

In an essay on ‘The Origins of Sex’, Conner Habib writes about the earliest life on earth, bacteria called prokaryotes who lived on an ozoneless earth:

“In the gaze of the Sun, the tiny prokaryotic innards were often too damaged to recombinate on their own. So these beings reached, in the [pri]mordial soup, for the ejected DNA of their dead kin, the floating pieces of bodies amongst them. They used their own enzymes in conjunction with the dead to repair themselves. This was the beginning of sex for living organisms.”

And for the controversial Lynn Margulis, who taught Habib:

“Sex began when unfavorable seasonal changes in the environment caused our protoctist predecessors to engage in attempts at cannibalism that were only partially successful. The result was a monster bearing the cells and genes of at least two individuals (as does the fertilized egg today). The return of more favorable environmental conditions selected for survival those monsters able to regain their simpler, normal identity. To do so, each had to slough off half or more of the ‘extra’ cell remains. (…) Cannibalistic fusion and its thwarting by programmed death became inextricably linked to seasonal survival and to individuality.”

From the 1950’s until he retired, Papa was an artist for the “adbusiness.” Simultaneously, he wrote infuriated tirades about the industry.

“The salesman is the gravedigger of our commercial civilization.”

“A wholly ephemeral institution…Ad agencies are in charge of promoting and merchandising our throw-away civilisation (…) professional hacks, make it their job to inflate language, deflate truth and sell cheap and expensive junk.”

My grandfather flagellates himself, but was it the trauma of losing everything in his youth that made him feel bound to a career that made him “rich?” Though he doesn’t mention that his wife, my grandmother, worked as a hairdresser, he certainly provided for his family. So perhaps it was his family, and by extension, I, who made it impossible for him to quit a career that didn’t align with his own ideals. So am I the parasite, two generations later, benefitting from his work without offering anything in return?

Did his “nervous caution” come from being an immigrant?

“I am a man apart from the mob, an alien among the indigenous, a lone traveler on the sidelines of life who sees the people march in step on the broad highway—but unable, or perhaps even unwilling, to join in

Is this a better way to understand the parasitism of all things? If we can imagine any parasite as ‘feeling’ guilty for not fully integrating and assimilating, Or a parasite who worries that they will never truly be an insider. A tape-worm who just wants to be one of the family with the probiotic stomach flora…Poor thing!

I called him Papa, while my mother called him Dad and my grandmother called him Howard. As an immigrant, I am told, he insisted on assimilating to use English as the primary language at home. Even when his own mother lived with them, for a time he refused to speak German. My mother laments the fact that his mother tongue was not passed down. However, I wonder about how erasure might function as it applies to epigenetic memory—as in, is the German language written into my genetic code as opposed to the German language? A sort of epigenetic Derridean erasure?

I have what I call a “porous dream-life.” It is relational. I attribute this ability to my grandmother and Papa’s wife, ‘Baba.’ She dreamt of his death at the very moment that it occurred miles away in a hospital bed. I have woken up and reflected on a dream where I was with someone, holding their hand, to later find out that what I was witnessing was their dream. Perhaps this is less “porous” and more invasive. When I bring my grandfather’s writings into my work, am I a host to him, or am I invading? Who is parasite and who is host?

This word, “porous,” feels right. It describes the boundaries as they truly are—navigable even as some things may be lost in filtration. In collaboration, inter-course, or exchange there is always some degree of loss. In order to truly collaborate one has to accept that their individuality must die to merge and become relational. So, since my grandfather is dead, what then? Is it a free-for-all? Or a ‘free-for-me’? Does true exchange require that I too have to die in some way? Whether it be in the giving of space to him, or perhaps in reckoning with his flawed ideas. The realization that while some of his writings are of interest to me, there is a lot of less-than-exciting content—bringing forth the inevitable truth that your (my) shit, too, does in fact, stink.

The term parasite comes from the Greek word parasitos meaning “person eating at another’s table.” Perhaps it is because I believe we always are in relation, “eating from another’s table.” I feel a meal is better when it is shared, when you greet and sit with the other. Or “behold” them as Silverman puts it. Of course, my grandfather can no longer sit with me at this table, but he set the table. And so from his table, I eat.

Papa:

“Recognition for a man’s knowledge should not be sought in mere tangible returns, nor in its rare, and momentary, flashes of awe-inspiring genius, but in its living continuity beyond the grave.” So I suppose, this in some way is my responsibility. I do not have the luxury of not reading his work. But luckily, since I am not a “man,” maybe I don’t need to worry about my life beyond the grave. I can be the ventriloquist making his little papier-mache dummy speak. This is much less daunting than pretending that my work stems from some miraculously unique place inside of me. The dummy has always been speaking. But a ventriloquist on stage alone is just a bad comedian and a dummy without a ventriloquist is just an inanimate doll.

References

- Serres, Michel. The Parasite. University of Minnesota Press, 2007, p.185.

- Silverman, Kaja. Flesh of My Flesh. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2009. Print.

- Ovid, and Mary M. Innes. „Book X – Orpheus and Eurydice.“ The Metamorphoses of Ovid. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1955. p 246. Print.

- Silverman, Kaja. Flesh of My Flesh. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2009. p 50. Print.

- ibid.p.46

- ibid. p.4